Cholerhiasis: A Definitive Guide for Patients, Caregivers & Clinicians

Cholerhiasis is a term many patients and online searches turn up when seeking information about severe digestive illness involving bile or intestinal symptoms. Although “cholerhiasis” itself is not a well‑defined clinical diagnosis in leading medical textbooks, the word appears in lay usage and some clinical discussions to refer either to cholera — a life‑threatening diarrheal infection — or to conditions related to bile, gallstones, and bile duct disease. Clarifying what people mean when they use the term “cholerhiasis” can help you understand the underlying medical conditions, their real causes, and how they are diagnosed and treated.

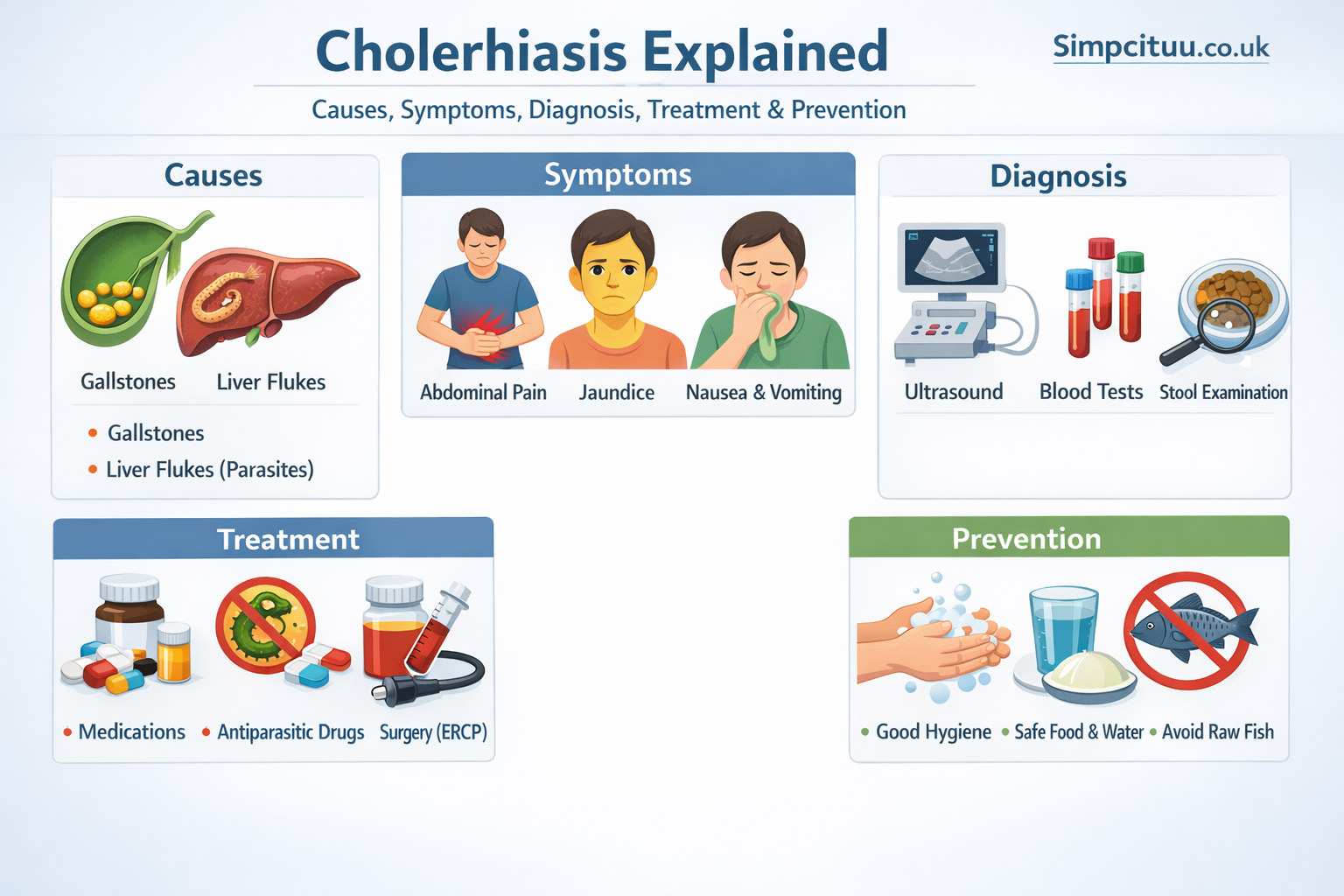

In this comprehensive article, we explore cholerhiasis from every angle: its definitions, causes, common symptoms, how clinicians think about it, diagnostic approaches, treatment pathways, prevention strategies, and common misunderstandings. Whether you’re writing for an audience that has encountered the term online or you’re trying to interpret clinical information about symptoms someone described as “cholerhiasis,” this guide will serve as your authoritative resource.

What “Cholerhiasis” Really Means

Most medical professionals do not recognize “cholerhiasis” as a formal diagnosis. There are three common possibilities when people use this word:

In online health writing, “cholerhiasis” is sometimes used as a synonym for cholera, a bacterial infection of the small intestine that causes sudden, severe diarrhea and rapid dehydration. The disease cholera is caused by Vibrio cholerae, and remains a major global public health concern in areas with unsafe water and poor sanitation.

Other times, “cholerhiasis” is a lay mis‑spelling or confusion with cholelithiasis, the medical term for gallstones — hardened deposits in the gallbladder or bile ducts that can disrupt the flow of bile and cause intense abdominal pain.

Some sources also connect “cholerhiasis” loosely with bile overproduction or discharge in an archaic sense, echoing terms such as “cholerrhagia” — excessive discharge of bile.

In practice, understanding the context of symptoms and history is key to interpreting what someone might mean by the term cholerhiasis. In this article, we cover both the bacterial illness (cholera) commonly intended by that word and the gallstone‑related conditions that people often confuse with it.

The Biology Behind Cholerhiasis‑Like Symptoms

Cholerhiasis‑type complaints — whether referring to severe diarrhea or gallstone pain — arise from two very different biological mechanisms:

In cholera, the bacterium Vibrio cholerae produces a toxin in the small intestine that triggers massive outflow of water and electrolytes into the gut lumen. This results in profuse, watery diarrhoea that can lead to life‑threatening dehydration within hours if untreated.

In gallstone‑related disease, solid stones form from components of bile — especially cholesterol — when the chemical balance of bile becomes disrupted. These stones can remain in the gallbladder or migrate to the bile ducts, leading to obstruction of bile flow, inflammation, and pain.

The similarity in language — with “choler” referring to bile in Greek root words — can confuse patients searching for information. But the underlying pathophysiology and clinical implications are very different between these categories.

Why the Term Cholerhiasis Is Confusing

One expert in medical communication noted that people use “cholerhiasis” most often as a spelling error, a non‑standard synonym for cholera, or confusion with similar terms like cholelithiasis. Because it does not appear in established clinical references, interpretation requires clarifying what condition is actually under discussion.

This distinction matters:

Clinically, cholera is an infectious disease caused by contaminated water or food and requires rapid rehydration therapy.

Gallstone disease (cholelithiasis) is a digestive system disorder related to bile composition and gallbladder function, often requiring imaging and sometimes surgical intervention.

Combining these under a single label like cholerhiasis can lead to misunderstanding about diagnosis and appropriate care. In this article, we separate these contexts and discuss them clearly.

Causes of Illness Commonly Referred to as Cholerhiasis

Underlying causes differ depending on the real condition intended:

Cholera (infectious diarrhoeal illness)

Cholera is caused by infection with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, typically transmitted through contaminated water or food. The bacteria thrive in environments where sanitation and clean water access are poor — a major public health challenge in many parts of the world.

The cholera bacterium produces a toxin in the small intestine that prompts epithelial cells to secrete large amounts of fluid and salts, leading to rapid and severe diarrhoea that can dehydrate the body in hours if not treated.

Gallstone Disease (Cholelithiasis)

Gallstones form when bile — a digestive fluid made by the liver and stored in the gallbladder — becomes chemically imbalanced. If bile contains too much cholesterol, bilirubin, or too little bile salts, microscopic crystals can form and grow into stones over time.

Risk factors for gallstone formation include older age, female sex, obesity and metabolic conditions, rapid weight loss, pregnancy, and genetic predisposition. These stones may remain silent or migrate into bile ducts, where they can block bile flow and cause inflammation and pain.

Here’s a comparative table summarizing key causes and mechanisms:

| Category | Primary Cause | Mechanism | Common Settings |

| Cholera | Vibrio cholerae infection | Bacterial toxin causes massive fluid secretion | Contaminated water/food, poor sanitation |

| Gallstones | Bile chemical imbalance | Crystallization of bile components | Metabolic risk factors, genetics |

| Bile discharge terms | Archaic bile overproduction terms | Excessive bile secretion | Rare clinical use |

Symptoms Attributed to Cholerhiasis

Because cholerhiasis is not a single medical entity, symptoms people report can fall into two broad patterns:

Symptoms of Cholera

People who develop cholera — the infectious condition most commonly referred to when lay writers use cholerhiasis — may experience sudden onset of profuse, watery diarrhoea, vomiting, and signs of dehydration.

Dehydration manifests as intense thirst, dry mouth, sunken eyes, reduced urine output, fatigue, and lethargy. Shock, electrolyte imbalance, and organ dysfunction can occur if fluids are not promptly replaced.

Symptoms of Gallstone‑Related Disease

Gallstone disease typically presents very differently. Patients may experience steady, severe pain in the upper right abdomen or mid‑abdomen, particularly after meals rich in fats. This pain — called biliary colic — can radiate to the back or shoulder and persist for thirty minutes to hours.

When stones block bile ducts, inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis), jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes), fever, and nausea may occur. These symptoms suggest complications that require urgent care.

Diagnosis: How Clinicians Approach It

Because “cholerhiasis” does not have a diagnostic code, clinicians instead apply well‑defined frameworks based on actual clinical presentation:

Diagnosing Cholera

Suspected cholera is diagnosed by testing a stool sample for Vibrio cholerae. Rapid testing tools may be used in outbreak settings to guide public health response. Clinical diagnosis also considers recent exposure to contaminated water or food sources and classic symptoms like rice‑water stools and dehydration.

Diagnosing Gallstone Disease

For suspected gallstone disease, ultrasound imaging is the first choice because it safely and reliably detects stones in the gallbladder. Blood tests may be done to assess liver function, inflammation markers, and signs of infection or obstruction.

Additional imaging like MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) or ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) may be used if bile duct stones are suspected.

Treatment Options: Best Practices

Treatment of Cholera

The most important aspect of cholera treatment is prompt rehydration to replace lost fluids and prevent shock. Oral rehydration solution (ORS) is effective in most cases, while intravenous fluids may be needed for severe dehydration. Antibiotics may shorten the illness in severe cases but are not the primary lifesaving intervention.

Treatment of Gallstones

Many gallstones do not require treatment if they cause no symptoms. When stones cause recurrent biliary pain or complications, surgical removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) is the most definitive treatment. Stone removal from bile ducts during ERCP may be necessary in complicated cases.

Prevention Strategies

Preventing cholera involves ensuring access to safe, treated water, proper sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and public health measures like surveillance and vaccination in high‑risk areas.

Preventing gallstone formation focuses on lifestyle and metabolic risk factors — maintaining healthy weight, balanced diet, regular exercise, and avoiding very rapid weight loss.

What Experts Say

“When lay terms like cholerhiasis appear in patient searches, it underscores the need for clear medical communication and education. Distinguishing infectious diarrheal diseases from biliary disorders ensures patients receive the right care at the right time.” — Medical Communications Specialist

Practical Examples & Real‑World Cases

In regions affected by flooding and disruption of water systems, public health teams often see spikes in cholera cases — a pattern sometimes reflected in online searches for “cholerhiasis” when communities lack clear terminology. Timely rehydration camps, oral vaccines, and safe‑water interventions dramatically reduce mortality.

In contrast, a middle‑aged woman with episodic right upper quadrant pain after fatty meals might search for “cholerhiasis” thinking it explains her symptoms. In fact, gallstone disease is likely, and imaging confirms stones requiring surgical management.

These scenarios show why understanding both contexts is critical for appropriate care.

Common Misconceptions

One frequent myth is that cholerhiasis is a unique disease entity. In reality, it’s a nonstandard term often used interchangeably with cholera or confused with gallstone conditions.

Another misconception holds that antibiotics alone cure cholera. While antibiotics aid recovery in severe cases, rehydration is the true life‑saving intervention.

Finally, people sometimes think gallstones must always be symptomatic; many individuals have silent stones that never cause symptoms.

Conclusion

Although “cholerhiasis” is not a formally recognized medical diagnosis, the term reflects two distinct clinical realities: cholera, a severe infectious diarrhoeal disease caused by Vibrio cholerae, and gallstone‑related biliary disorders such as cholelithiasis. Understanding the differences — in causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment — helps patients and caregivers find accurate, life‑saving information and seek the appropriate care.

By clarifying terminology and focusing on evidence‑based medical knowledge, this definitive guide has equipped you with a clear, expert understanding of what people commonly mean when they encounter the word cholerhiasis.

FAQs About Cholerhiasis

What is cholerhiasis?

Cholerhiasis is not a formal medical term but is commonly used in lay contexts to refer either to cholera — a bacterial diarrheal disease — or confusion with gallstone disease.

What causes symptoms associated with cholerhiasis?

Symptoms linked to cholerhiasis‑like illness are caused by either infection with Vibrio cholerae (cholera) or gallstones disrupting bile flow, depending on the clinical context.

How is cholerhiasis diagnosed?

Doctors do not diagnose cholerhiasis per se; instead they identify the underlying condition — cholera is diagnosed with stool testing for bacteria, while gallstones are seen on imaging like ultrasound.

Can cholerhiasis be prevented?

Preventing cholera (often implied by cholerhiasis) requires safe water, sanitation and hygiene measures. Preventing gallstone disease involves healthy lifestyle choices to balance bile chemistry.

Is cholerhiasis life‑threatening?

When used to describe cholera, the condition can be life‑threatening if dehydration is not treated promptly. Gallstone disease can complicate into serious infections or blockages if not managed properly.